exhibits

This Historical Society produces changing exhibits at the Old Brick Schoolhouse. Past exhibits have included topics such as Schools, Gold Mines, Logging, Camp Life, The Woolen Mill, and Bridgewater’s Civil War Soldiers. The current exhibit (2023-2024) is “The Message Gets Through: W.A. Perkins and the Southern Vermont Telephone Company.”

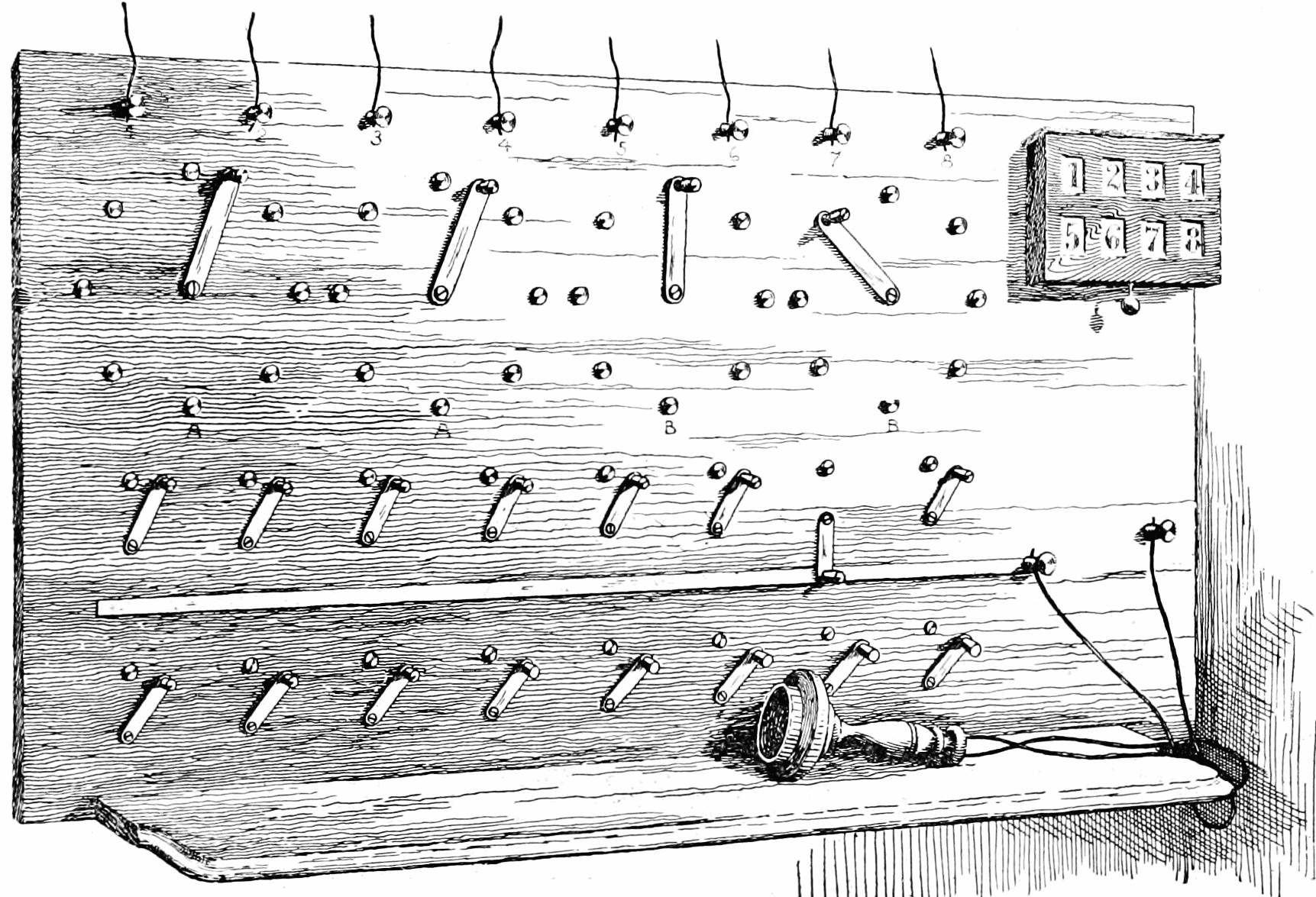

THE SWITCHBOARD

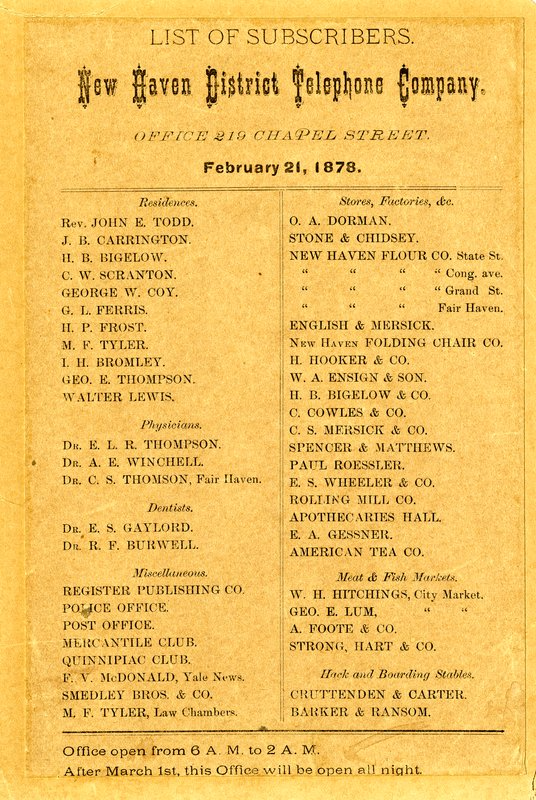

In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell received a U.S. Patent for the first practical telephone design, ushering in one of the most revolutionary devices of the late 19th century. The earliest telephones, however, were extremely limited: they allowed for communication between two receivers, but only if they were directly connected by a single wire. It wasn’t until January 1878 that a New Haven inventor by the name of George Willard Coy created the world’s first commercial telephone exchange, which allowed a single telephone to connect to multiple lines through a central switchboard.

Several months earlier, Coy had attended a lecture in New Haven given by Bell himself, where the inventor first discussed the concept of a central exchange which could, in theory, provide access to multiple telephones using only one connected line. Coy, a Civil War veteran and longtime telegraph operator and office manager, convinced a pair of local investors, Herrick P. Frost and Walter Lewis, that he could make Bell’s idea a reality, and with their help, purchased a storefront on State Street in downtown New Haven that soon became home to the world’s first commercial telephone exchange.

The inventive Coy proceeded to build a primitive switchboard from what appeared to be little more than spare parts, including carriage bolts, teapot handles, and a type of metal wire normally used to make ladies’ undergarments. Subscribers to the exchange service would pick up their receivers and speak to an operator, who could then manually connect their line to the telephone of any other fellow subscriber. With this simple setup, a telephone owner only required one single line to be installed — from their home to Coy’s central exchange — in order to reach dozens of different subscribers.

On January 28, 1878, Coy’s telephone exchange, under the aegis of the District Telephone Company of New Haven, went live, ushering the world into a new age of live, long-distance, and convenient communication. For its first month of operation, the District Telephone Company had twenty-one subscribers — mostly businesses and government offices — who paid $1.50 a month for the service. Less than a month later, the number of subscribers had more than doubled, inspiring Coy to publish the world’s first telephone directory on February 21 — a one-page listing of all fifty subscribers on his exchange. Most of these were businesses and listings such as physicians, the police, and the post office; only eleven residences were listed, four of which were for persons associated with the company. The switchboard quickly became a fundamental feature of telephone communications the world over, and Coy’s company, which renamed itself the Southern New England Telephone company in 1882, would become one of New England’s most influential companies of the 20th century.

From: Today in Connecticut history and Wikipedia

An illustration of an early telephone switchboard, from a 1907 issue of Popular Science magazine.

THE SOUTHERN VERMONT TELEPHONE COMPANY

Click on photos to view as slide show

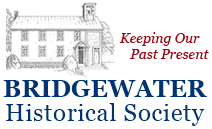

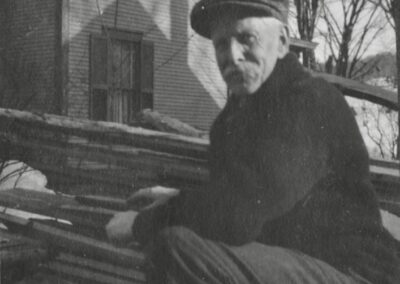

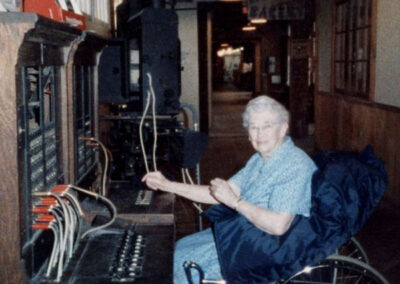

Winfred A. Perkins, 1863-1936, of Bridgewater, started his career as a “telegrapher” in White River. He incorporated the Southern Vermont Telephone company in 1907, commencing business in Bridgewater, in 1909. His wife Nellie, served as one of the Directors as well as the sole operator from 1912 until her retirement. The telephone office was in their home on Main Street in Bridgewater.

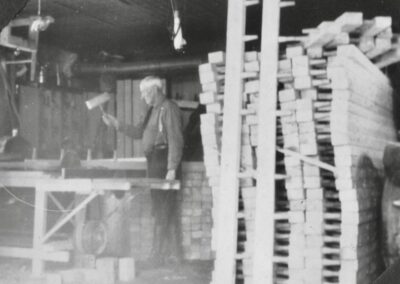

In 1915, he built a barn in their backyard, to house the construction of the crosstrees for telephone poles, as they were enlarging the company. The photos show his working on the building as well as fabricating the cross trees.

His plans for expansion are shown on his hand drawn map. By 1921, the company was serving Woodstock, Plymouth, Sherburne, Reading, Bridgewater, and Ludlow.

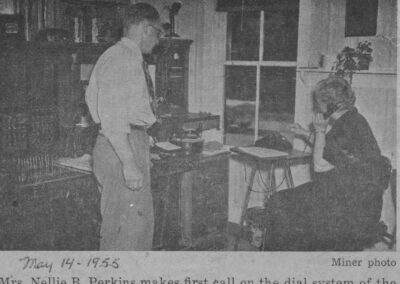

In 1955, Nellie Perkins was the first in Bridgewater to use a rotary dial telephone.

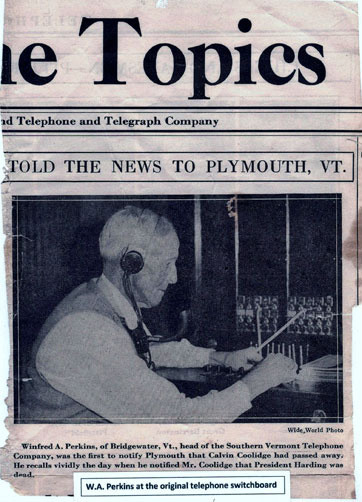

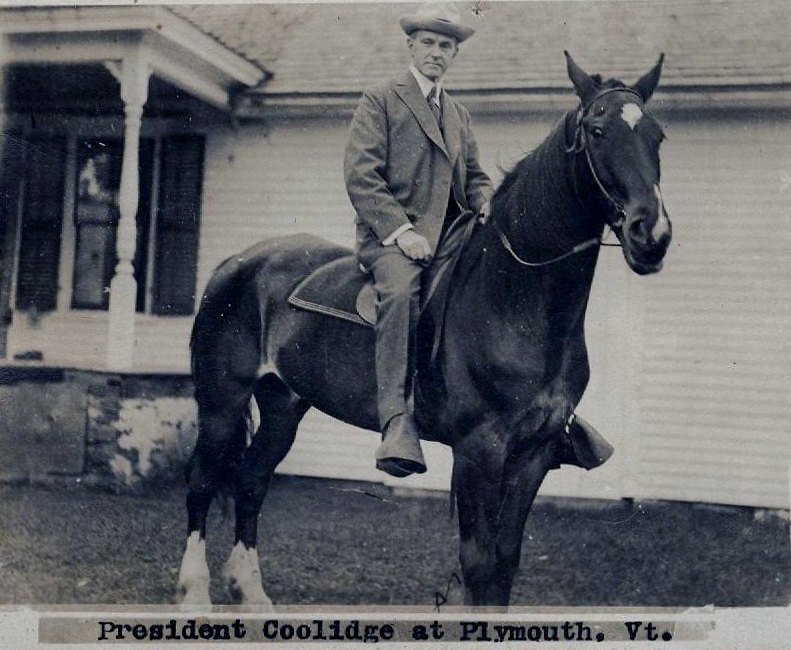

On August 2, 1923, Nellie Perkins received a call that President Harding had died. John Coolidge would not have a telephone at the farm, so W.A. Perkins drove to Plymouth Notch to tell the Coolidge family. He arrived at 12:30 PM and the President was sworn in at 2:30 AM on August 3rd, 1923.

ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF THE CALVIN COOLIDGE PRESIDENCY

Debt, Tax, and Budget Reductions

- National debt lowered from $22.3 billion in 1923 to $16.9 billion in 1929.

- Harding/Coolidge/Mellon Tax Cuts: After years of very high wartime tax rates, rates were reduced significantly under the Revenue Acts of 1921, 1924, and 1926, especially the latter, which was the crowning achievement of Coolidge tax program. The combined top marginal normal and surtax rate declined from 73 percent to 58 percent in 1922. In 1924, the top tax rate decreased to 46 percent (income over $500,000). The top rate was only 25 percent (income over $100,000) from 1925 to 1928, and then fell temporarily to 24 percent in 1929. It is also worth noting that numerous “nuisance” taxes, such as on cars and theatre tickets, were eliminated.

- Federal budget reduced from $5.1 billion in 1921 to $3.1 billion in 1929.

Significant Legislation of the Coolidge Administration

- World War Adjusted Compensation Act of May 19, 1924, also known as the Soldiers’ Bonus Act promised veterans compensation for wages lost during their World War I service. Payments, however, were not going to be issued until 1945.

- Foreign Service Act of May 24, 1924, also known as the Rogers Act merged the Department of State’s Diplomatic Service and Consular Service—separate institutions since the nation’s earliest days—into the United States Foreign Service.

- Indian Citizenship Act of June 2, 1924 granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the U.S.

- Immigration Act of May 26, 1924, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act established National origin quotas as a permanent basis for U.S. immigration policy.

- Revenue Act of June 2, 1924. The Revenue Act of 1924 was part of the Mellon Plan (The Mellon Plan was proposed in 1924 and became the Revenue Act of 1924) to lower tax rates but included a gift tax for the wealthy. The law also established the U.S. Board of Tax Appeals.

- Protection of Forest Act of June 7, 1924, also known as the Clarke-McNary Act made it much easier for the Forest Service to buy land from willing sellers within predetermined national forest boundaries. It enabled the Secretary of Agriculture to work cooperatively with State officials for better forest protection, chiefly in fire control and water resources.

- The United States Arbitration Act of Feb. 12, 1925, also known as the Federal Arbitration Act seeks to ensure the validity and enforcement of arbitration agreements in any “maritime transaction or . . . contract evidencing a transaction involving commerce.” In general, the FAA evidences a national policy favoring arbitration.

- Revenue Act of February 26, 1926 addressed objections to the Revenue Act of 1924 by eliminating the gift tax and and ended public access to federal income tax returns and reduced the maximum individual tax rate from 40% to 25%. The Revenue Act of 1926 also reduced inheritance and personal income taxes and cancelled many excise taxes.

- Public Buildings Act of May 25, 1926, also known as the Elliot-Fernald Act was a statute which governed the construction of federal buildings throughout the United States, and authorized funding for this construction.

- Air Commerce Act of May 20, 1926 placed responsibility for aircraft, pilots and airlines with the government.

- River and Harbor Act of January 21, 1927, authorizing the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway

- The McFadden-Pepper Act of Feb. 25, 1927, allowed a national bank to operate branches to the extent permitted by state governments for state banks in each state.

- Radio Act of February 23, 1927 created Federal Radio Commission. Transmission facilities, reception, and service would be equal. Although the “Public” at large owned the radio spectrum, individuals would be licensed to use it; Licenses would be granted based on the public interest, convenience, and necessity

- Mississippi River Flood Control Act of May 15, 1928 authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to design and construct projects for the control of floods on the Mississippi River and its tributaries as well as the Sacramento River in California.

- Merchant Marine Act of May 22, 1928, also known as the Jones-White Act is a United States law to stimulate private shipbuilding in the United States and to assist the merchant marine financially in being competitive in the emerging global market.

- Revenue Act of May 29, 1928 gave the the Joint Committee’s authority was extended to the review of all refunds or credits of any income, war-profits, excess-profits, or estate or gift tax in excess of $75,000.

- Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928. The Kellogg-Briand Pact was a treaty, signed in Paris on August 27, 1928 between the United States and 62 other nations, that was inspired by the belief that diplomatic agreements could put an end to wars.

Sources: Calvin Coolidge Foundation, History for Kids, Library of Congress, Wikipedia

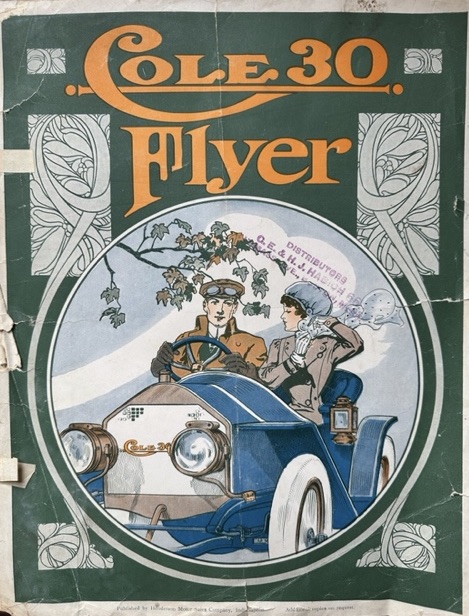

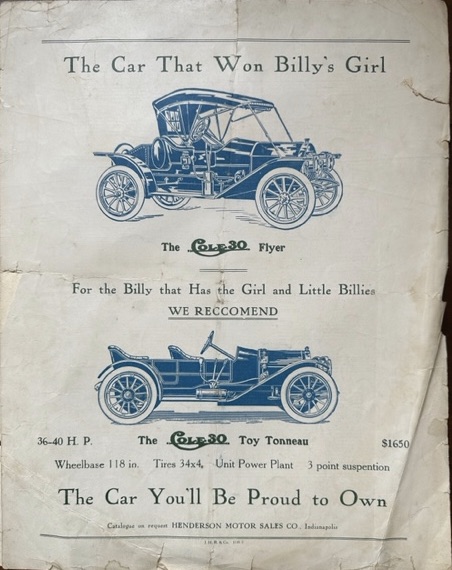

THE COLE MOTOR CAR COMPANY

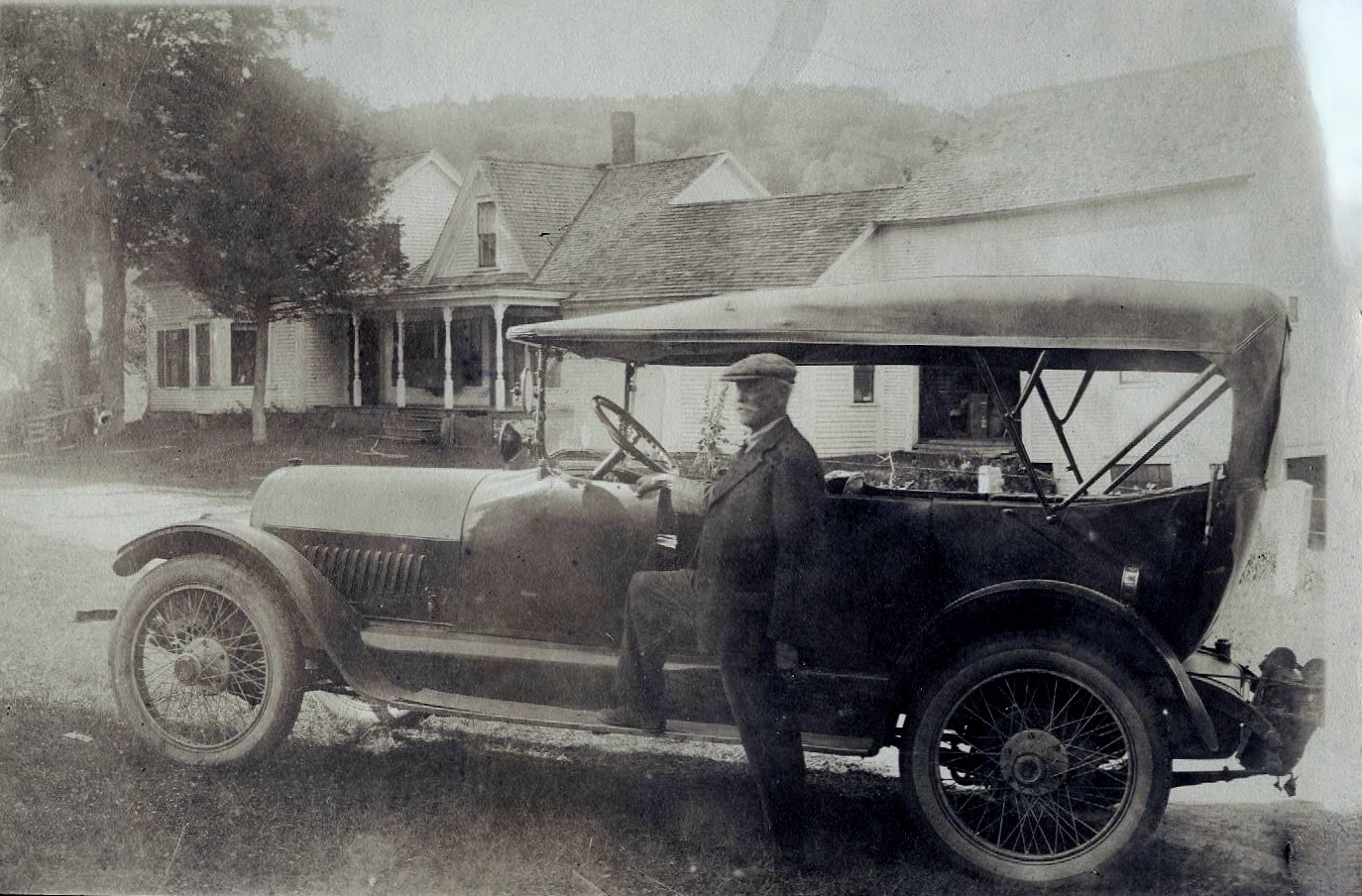

W. A. Perkins and his Cole 8

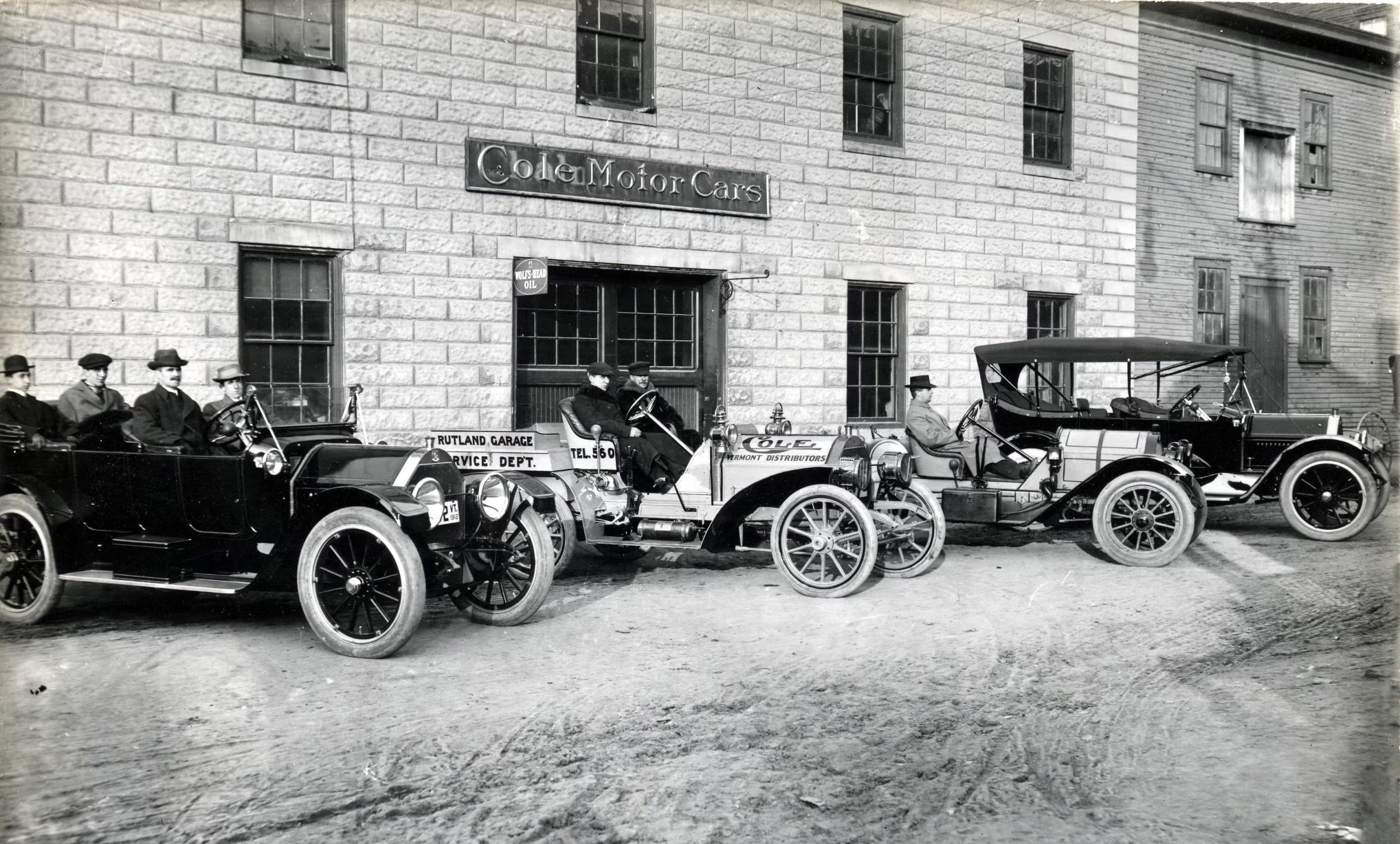

Cole Motor Cars Dealership in Rutland Vermont

Sheet Music

On August 2nd, 1923, Nellie Perkins, telephone switchboard operator at Southern Vermont Telephone in Bridgewater, received a call with an important message for Vice President Calvin Coolidge; President Harding had died. As there was no telephone at the Coolidge homestead in Plymouth, W.A. Perkins, Nellie’s husband, drove his 1918 Cole-8 to Plymouth to deliver the message.

What was a Cole-8 automobile?

The Cole Motor Car Company was an early automobile maker based in Indianapolis, Indiana. Cole automobiles were built from 1908 until 1925. They were quality-built luxury cars. The make is a pioneer of the V-8 engine.

In 1904, Joseph J. Cole (1869–1925) bought the Gates-Osborne Carriage Company and soon renamed it the Cole Carriage Company. There, he built his first automobile. It was a high-wheeled motor buggy with a two-cylinder engine.

In June 1909, Cole Carriage Company was reorganized as the Cole Motor Car Company and developed a conventional small car, the Cole Model 30. It had a two-cylinder engine that delivered 14 HP. It rode on a 90-inch wheelbase. The only body style was a runabout offered with 2, 2/4, or 4 seats at $725, $750, or $775, respectively.

At the end of 1909 a completely new car appeared as a 1910 model. It was also dubbed the Series 30 referring to its new 30 HP, four-cylinder engine. The wheelbase was 108 inches. There were four open body styles. Least expensive was the Tourabout at $1,400, two touring cars and a runabout called the “Flyer”, were $1,500 each.

A Series 40 replaced the 30 in 1912. This car had a 122-inch wheelbase. It had a more powerful 40 HP four-cylinder motor. Prices started at $1,885 for each of the four open body styles. There were also a “Colonial Coupe” for $2,500 and two limousines at $3,000 and $3,250. These prices brought Cole well into the luxury car market.

For 1913, Cole expanded to no less than three model lines: The Series 40, now on a 116-inch wheelbase, a 50 HP Series 50 that got the previous 40 chassis, and their first six-cylinder car. Although designated the Series 60, it had in fact 40 HP. Wheelbase was huge at 132 inches. Prices were $2,485 for one of the open body styles but went up to $3,000 for a coupe and an astronomical $4,250 for a 7-passenger Berline-Limousine. The Series 40 was cut to two open styles, a roadster and a touring car, for $1,685 each. In the Series 50, the same body styles were offered, plus a toy tonneau, at $1,985 each. Further, Coles got electric ignition and lighting for the first time.

1914 brought several changes. Series 40 and 50 were replaced by a new Model Four, a 4-cylinder car with 28.9 HP and a wheelbase of 120 inches. Offered were a roadster, a touring car and toy tonneau at $1,925 each, plus a 3-passenger coupe for $2,350. The 6-cylinder car also was renamed the Six. It got 43.8 HP with a wheelbase of 136 inches. There was a big 7-passenger touring car, plus the usual roadster and toy tonneau, each at $2,600. A coupe could be had for $3,000 and a limousine for $4,000.

Sales had been low in 1914, so Cole reduced prices for 1915. Further, there were new designations – again – and even some new cars, too. The Four was now called the Standard 4-40. It lost the toy tonneau, and the remaining cars were offered much cheaper: $1,485 for the two open cars and $1,885 for the coupe. The Six was split into two ranges. The smaller Model 6-50 got a 29 HP engine and a 126-inch wheelbase. It offered a 4 and a 7-passenger touring car $1,865, a roadster at $2,465 and the coupe at $2,250. The new Big Six 6-60, built on the previous year’s 136-inch chassis, got a powerful 40 HP engine, prices for the Roadster and 7-passenger touring car were $2,465, the coupe at $2,750, and limousine at $3,750.

Cole could shuffle with models and engines the way it did for two reasons: The first was that until 1915, the company refused to offer their cars on a yearly model change but relied on series that were replaced when management felt the necessity for it.

The second reason was that the Cole was an assembled car; that means that all important components such as engine, clutch, transmission, axles etc. were bought from outside sources. For Cole, this was not only the simpler way to build a car, but Joseph Cole thought that specialized suppliers could give more attention to their items. Thus, he preferred the term “standardized car” over the usual “assembled car”.

Big news came in mid-1915: Only one year after Cadillac had pioneered the V-8 engine, Cole brought out its own V-8 powered automobile and would stay with it until the very end of the make, dropping its Fours and Sixes after 1916. This engine had a displacement of 346.3 c.i. and delivered 39.2 HP. It was built by Northway, then a division of General Motors that also manufactured the V-8 for Cadillac. The car was named the Model 8-50. It had a 127-inch wheelbase. Five body styles were available at prices between $1,785 and $3,250.

There were few changes for 1917. The car was now called the Model 860. There were five body styles at about the same price level. Some of them received quite flamboyant designations such as “Tuxedo Roadster”, “Tourcoupe”, and “Toursedan”, of which a “Foredoor Toursedan” existed, probably a 2-door sedan.

The new kind of marketing became even more apparent in 1918. Advertising slogans were “There’s a Touch of Tomorrow In All Cole Does Today” or “Did You Ever Go Ballooning in a Cole?”, the latter referring to the adoption of balloon tires as an option that year. The car was advertised as the “Aero-Eight”. There were only three body styles left, a roadster, a “Sportster” and the touring car. They cost $2,395 each and seated 2, 4, and 7 passengers, respectively. The cars also became more fashionably styled.

Cole opened new, wider production facilities in 1922. However, sales went down rapidly, mainly because of a short but severe recession. Although there were more models to choose from and prices were reduced drastically (most to a level under that of 1918 / 1919), only 1,722 cars were built of the Model Aero Eight 890, as the car was called that year. The wheelbase was increased by a quarter inch, and the frame ends were split. The Sportcoupe had a weight of 4,155 pounds. The car was priced at $3,385 with a 75-mph speedometer.

Innovations in 1923 for the Series 890 Cole were stylish drum-type headlights, cowl ventilation, and a new windshield with an adjustable upper half on open cars. Other elegant details were wire wheels instead of the previously used “artillery wheels” with fashionable disc wheels on the option list. For this year only, some cars had an added sporty touch with running boards that did not span the whole length, leaving the chassis-mounted spare wheels “free”. Still, with eight types of bodies, prices for open cars were slightly up while those for closed cars remained the same. The most expensive 1922 model, the $4,185 “Tourosine”, was gone as were all those strange names, with the exception of the “Sportsedan”. Only 1,522 cars left the factory that year.

In this situation and without any debts yet, J. J. Cole decided to liquidate his company rather than risking his fortune by going on. So, it is no wonder that the Model 890, now also called “Master” series, went little changed on the show room floors. Full-length running boards were back on all models. There were seven body styles, again sharply reduced to prices as low as $2,175 for open bodies, $2,750 for a coupe and $3,075 for other closed cars. A Cole was honored to pace that year’s Indy 500 race.

Before the curtain finally fell, there were five cars available for 1925. Balloon tires were now standard equipment, and the cars got new two-piece rear bumpers, called “bumperettes”. Although Joseph Cole began liquidating his firm early in 1925, 607 cars left the factory. He died suddenly of an infection on August 8, 1925, shortly before liquidation was finished.

Source: Wikipedia